Challenges, profile, competencies and training of the 21st Century European Prison Officer

Prison officers in Europe

In Europe[1], there are nowadays, more than 588 940 citizens under the custody of the prison service[2]. Every day more than 203 772 prison officers all over the 28 EU member states work to ensure safety to society and to provide opportunities to inmates that will ease their reinsertion process back to society.

Regardless of their engagement towards this noble mission, the organization of the prison system is dependent of a multiplicity of actors that compel to a continuous balance of apparent conflicting needs, objectives and interests (psychologists, educators, psychotherapists, social workers, administrative staff, teachers, trainers, workshop masters, nurses and doctors to prison officers – military or civilians – prison governors and their deputies. The co-existence of different sub-cultures and different visions of the penitentiary treatment is often the origin of internal conflicts (explicit or latent) between prison directors, re-education staff and security staff/prison officers (the majority of staff in prison systems).

As in hospitals, in which the organisation of the work developed and the qualification of its experts has a direct consequence in the life-death or wellbeing of patients, the work and specific action of prison professionals has a direct impact in inmates’ life, their attitudes and behaviours while in prison and after release.

A dual role facing multiple challenges

It is not possible to understand the dynamics that occur in prisons and the experience of prison life for prisoners without an understanding of the role of the prison officer. According to the European Commission’s ESCO[3] “Prison officers supervise inmates in a correctional facility and ensure the security and peace-keeping in the facility. They perform checks and searches to ensure compliance to regulations, monitor visitations and the activities of inmates as well as participate in programs of rehabilitation and ensure records maintenance”[4].

The complexity of the dual and conflicting role of the prison officer as well as its impact in the relationship with inmate’s, stress and burnout has been described and discussed since a long time, as a problem emerging from conflict between two sets of ethical norms: those associated with community protection and justice versus norms related to offender/defendant well-being and autonomy. This situation is known to create “an immature” coping between prison staff and inmates, that foster high levels of stress and sometimes potentially aggressive and harmful behaviours. No matter if working in private or publicly operated prisons, prison officers are requested to respond effectively to complex phenomena that often lead to the degradation of the material conditions of detention – thus conditioning everyone living inside prison walls. Overcrowding, ageing and the increase in prison population (in some countries); gangs and organized crime; extremism and in-prison radicalisation; inmates’ mental illness; the overall degradation of the social and psychic health and increasingly dangerous behaviours of the inmates; are, among others, some of current challenges that prison officers face.

Technology and the need for digital skills in prisons

Mobility and the use of different technological communication and learning solutions soared in the past decade. The current landscape regarding the use of technology solutions that support prison and probation management but also the inmate’s education and rehabilitation is varied. While technological solutions that support the daily management of a prison and offenders become more popular to prison administrations, the use of technologies that support education, that allow the contact with family, friends, community institutions or public services – e.g., e-learning systems, self-service systems, the use of tablets, controlled internet access, video-visitation, and advanced controlled communication – still face substantial barriers to be implemented. Nevertheless, it can safeguard officers and inmates’ general wellbeing, while achieving a high level of efficiency and effectiveness of practices developed within correctional organisations. Regardless of existing budget constraints, barriers often result from old and unchanged legal frameworks and prison regulations; from the lack of understanding of the advantages of the use of these technologies both for the inmates and for prison operation; resistance from prison staff to the use of technology that supports (but also monitors) their activity; and the beliefs in myths or obsolete security ideas about the use of technology in prisons in general and the use of technology in prison by inmates, in particular. However, it is stated that prisons would be wise to adapt sooner than later since, similarly to other organizations, they monitor every individual who operates or moves through them via a corporeality, technology-based interface encouraging flexibility of movement while retaining high – but discrete – levels of security.

In Europe, prison administrations such as Belgium, the Netherlands, England and Wales, Scotland, Austria and some German landers have introduced technological solutions that allow inmates to have access to digital services and promote autonomy and empowerment on some daily decisions. The introduction of technology in prisons reinforces the need to development of digital skills and to rethink the prison officer’s role as it may introduce substantial changes in the way prison operation is run but also in the relationship between professionals and professionals and inmates.

The need for training of correctional officers

Despite all the challenges mentioned above, and being commonly referred as essential both in security and rehabilitation, prison officers often lack proper initial and continuous training. The situation in Europe evidences a big difference in policies and practice. Recruitment and selection differ in every member state regarding the personal profile, basic levels of education and training of the candidates to become prison officers. Initial training can differ from 50 days training[5] up to a 3 year’s university-level degree[6] depending on the Member-state and continuous training is very limited or inexistent. Also, the content of the training varies, being reinforced the development of different competencies not always aligned with the desired balance between security and support to rehabilitation and reintegration.

The situation described inhibits the mobility of professionals between Member-states and hinders the implementation of the Framework decision 2008/909/JHA on the application of the principle of mutual recognition to judgments in criminal matters. Furthermore, the Council of Europe[7]recommends that “prison services should have their own induction and advanced training curricula, which correspond to the role and tasks of the different categories of their staff and to the aim and purpose of their work “and that “there should be opportunities for joint prison and probation staff training and for training with staff from other criminal justice agencies in order to encourage inter-agency and inter-disciplinary work. Such cooperation will promote the mutual goals of the respective services, i.e. to promote public safety, rehabilitation and reintegration.”

The need for systematic training of prison staff is also suggested by the European Parliament recalling that “social recognition and systematic training of prison staff are essential to ensure secure and appropriate detention conditions in prisons” and encouraging the Member States to “share information, to exchange and apply good practices and to adopt a code of conduct and ethics for their prison staff” calling for a General Assembly of Prison Administrations, which should include representatives of prison staff. Also, the European Parliament resolution on its resolution of 5 October 2017 on prison systems and conditions (2015/2062(INI)[8] acknowledges that “penitentiary staff carry out an essential function on behalf of the community and should enjoy conditions of employment befitting their qualifications and which take account of the demanding nature of their work” and that “considering the difficult and delicate nature of their activity, measures such as better initial and continuous training of prison staff, an increase in dedicated funding, the sharing of best practices, decent and safe working conditions and an increase in staffing levels are essential to ensure good detention conditions in prisons; whereas continuous training would help support prison staff in addressing new and emerging challenges such as radicalisation in prison”. Whereas “motivated, dedicated and respected prison staff are a precondition for humane detention conditions and hence for the success of detention concepts designed to improve the management of prisons, successful reintegration into society, and the reduction of risks of radicalisation and recidivism”.

The European Parliament also recalls “the fundamental role of social dialogue with prison staff as well as the need to involve staff via information and consultation, especially when developing new detention concepts designed to improve prison systems and conditions, including those aiming at containing radicalisation threats; and Calls on the Member States to ensure regular dialogue between prisoners and prison staff, as good working relationships between staff and prisoners are an essential element of dynamic security, in de-escalating potential incidents or in restoring good order through a process of dialogue.”

The PO21 Sector Skills Alliance

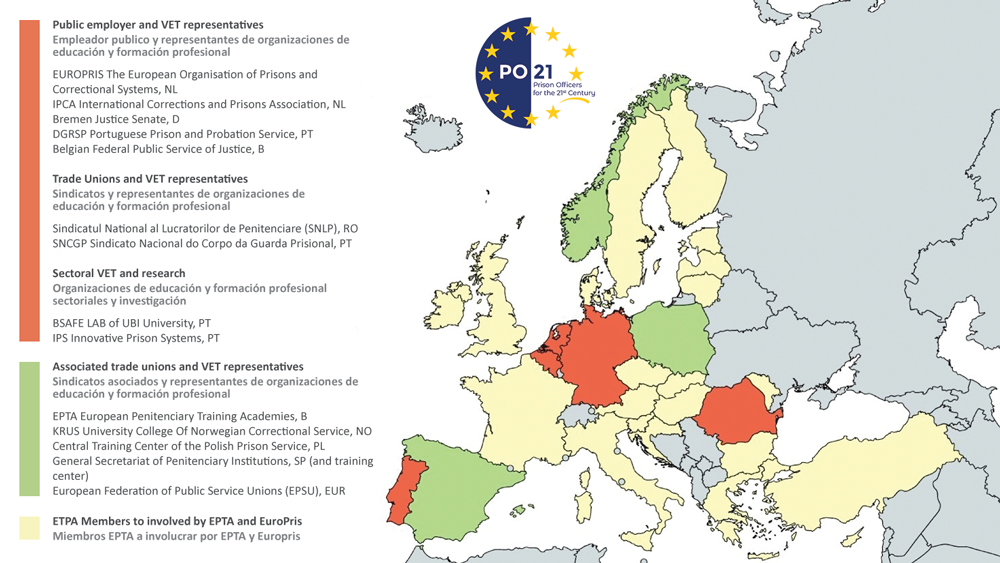

The PO 21 Sector Skills Alliance is funded by the ERASMUS Plus Programme[9] of the European Commission and is developed by sectoral representatives (prison administrations, trade unions, VET and research organisations, and representatives of correctional private and public sector members) whose primary concern is the advancement of the correctional sector. Therefore, the PO 21_ European Prison Officers for the 21st Century Sector Skills Alliance aims to:

- Develop a strategic approach to sectoral skills development through the creation of a partnership for the sustainable cooperation between prison administrations and correctional academies, trade unions, and other sectoral representatives;

- Identify existing and emerging skills needs for prison officers, also feeding this intelligence into the European skills panorama;

- Strengthen the exchange of knowledge and practice between education and training institutions and correctional sector actors;

- Promote relevant sectoral qualifications and support agreement for their recognition;

- Build mutual trust, facilitating cross-border certification and therefore easing professional mobility in corrections, and increasing recognition of qualifications at the European level;

- Adapt vocational education and training provisions to skills needs, focusing both on prison officer job-specific skills as well as on key competences;

- Promote qualification standards for work-based learning (range of knowledge, skills and competencies that are to be achieved through work-based learning or learning on-the-job).

- Plan the progressive roll-out of project deliverables leading to systemic impact in the form of constant adaptation of VET provision to skill needs, based on sustained partnerships between providers and key labour market stakeholders at the appropriate level (“feedback loops”).

A particular focus is given to digital skills since they are increasingly changing the operational activity of POs, as well as the way professionals relate with each other and relate with inmates in prisons.

PO21 is led by the BSAFE LAB of the UBI University (a specialized research lab focused on the development of research and training in the areas of justice, law enforcement and public safety) together with IPS_Innovative Prison Systems[10] (renowned research and advisory firm specialised on the development of correctional services); EuroPris[11] the European Organisation of Prisons and Correctional Systems is the sectoral representative of European prison systems – representing 32 prison administrations (employers) and correctional academies (VET organisations). EuroPris also represents EPTA[12], the European Prison Training Academies network. With a broader geographical focus towards the advancement of corrections around the world, ICPA[13] is the International Corrections and Prisons Association represents 35 correctional services and 40 private companies that run private prisons (representing also both the employers and VET organisations). Furthermore, ICPA has extensive experience of correctional staff training in different parts of the world[14].

This Sector Skills Alliance also counts with government agencies (correctional services) such as the Bremen Senate of Justice and Constitution from Germany (representing the prison administration as employer, as well as it’s training academy); the Portuguese Prison and Probation Service (and its VET centre); the Belgian Prison Service (and its VET academies); and with trade unions representatives (representatives of the Prison Officers) such as the Sindicatul Național al Polițiștilor de Penitenciare (6500 penitentiary police officers as members) from Romania – also a member of EPSU European Federation of Public Service Unions – and the SNCGP Sindicato Nacional do Corpo da Guarda Prisional from Portugal (representing 3636 PO’s).

Other organisations such as the University College of the Norwegian Correctional Service (KRUS), the Central Training Center of the Polish Prison Service, the Spanish General Secretariat of Penitentiary Institutions, among other sectoral organisations have demonstrated their interest to join the Sector Skills Alliance as associated partners[15].

There is a common understanding among the partners that the present and future challenges that a PO faces every day require a different set of skills and behaviours than the ones for which they have been trained for. Partners also acknowledge that there is also an urgent need to agree on the initial and continuous vocational education and training that should be provided to prison officers in the future – regarding the learning objectives, content, length of the training courses, and recognition of competences that may foster mobility throughout the European Union.

During the next three years, the PO 21 Sector Skills Alliance and associated partners will work together to reach the PO21 objectives. If you would like to involve your organisation in these important discussions and benefit from its results from an early stage, please feel free to visit our website https://www.prison-officers21.org/ and fill the registration form.

[1] Refers only to the Member States of the European Union.

[2] Council of Europe Annual Penal Statistics SPACE I – Prison Populations Survey 2016. Updated on 7th February 2019. Available online at http://wp.unil.ch/space/space-i/

[3] ESCO is the multilingual classification of European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations and is part of the Europe 2020 strategy. The ESCO classification identifies and categorizes skills, competences, qualifications and occupations relevant for the EU labour market and education and training. It systematically shows the relationships between the different concepts.

[4] ESCO European Skills, Competences and Occupations: http://data.europa.eu/esco/occupation/3327a087-cd36-4b02-ac1b-6455f59f9312

[5] As it is the case in Belgium.

[6] As it is the case in Norway.

[7] Draft Guidelines regarding recruitment, selection, training and development of prison and probation staff. European Committee on Crime Problems (CDPC) and the Council for Penological Co-operation (PC-CP). https://rm.coe.int/pc-cp-2018-14-e-rev-draft-guidelines-training-staff/16808e2d72

[8] http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P8-TA-2017-0385+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN

[9] Sector Skills Alliances aim at tackling skills gaps with regard to one or more occupational profiles in a specific sector. They do so by identifying existing or emerging sector-specific labour market needs (demand side), and by enhancing the responsiveness of initial and continuing vocational education and training (VET) systems, at all levels, to the labour market needs (supply side). More information available at https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/erasmus-plus/actions/key-action-2-cooperation-for-innovation-and-exchange-good-practices/sector-skills_en

[10] IPS Innovative Prison Systems is a trademark of QUALIFY JUST IT Solutions and Consulting. www.prisonsystems.eu

[11] www.europris.org

[12] www.epta.info

[13] www.icpa.org

[14] ICPA is a non-governmental organisation in Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations.

[15] Associated partners may contribute to the activities of the Sector Skills Alliance. They are not subject to any contractual requirements because they do not receive funding from the European Commission.

References

Liebling, A. (2007) «Prison suicide and its prevention». En Jewkes, Y. (Ed.). (2007). Handbook on Prisons, chapter 18. Londres: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203118191

Arnold, H.; Liebling, A. y Tait, Sarah (2007) «Prison officers and Prison culture» en Jewkes, Y. (Ed.). (2007). In Handbook on Prisons, chapter 20. Londres: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203118191

Thomas, J.E. (1974) The prison officer: A conflict in roles. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Volumen 18, Issue 4, August 1974, pages 259-262

Hepburn, J. (1980) Role in conflict in Correctional Institutions – An Empirical Examination of the Treatment-Custody Dilemma Among Correctional Staff. Criminología, Vol. 17 Iseo 4 February 1980. Páginas 445-459. American Society of Criminology.

Liebling, A. (2011). Distinctions and distinctiveness in the work of prison officers: Legitimacy and authority revisited. European Journal of Criminology, 8(6), 484–499. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370811413807

Williams, T. A. (1983). Custody and Conflict: An Organizational Study of Prison Officers’ Roles and Attitudes. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 16(1), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/000486588301600105

Howard League for Penal Reform (2017). The role of the prison officer Research briefing. Howard League for Penal Reform. https://howardleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/The-role-of-the-prison-officer.pdf

Ward, T. (2013). Addressing the dual relationship problem in forensic and correctional practice. Aggression and Violent Behavior, ISSN: 1359-1789, Vol: 18, númber: 1, page: 92-100.

La Vigne, N. (2017) Harnessing the Power of Technology in Institutional Corrections. NIJ Journal. Issue 278, May 2017.

Harne, J. (2017) Identifying Technology Needs and Innovations to Advance Corrections. NIJ Journal. Issue 278 May 2017.

Jackson, Brian A., Joe Russo, John S. Hollywood, Dulani Woods, Richard Silberglitt, George B. Drake, John S. Shaffer, Mikhail Zaydman, y Brian G. Chow, Fostering Innovation in Community and Institutional Corrections: Identifying High-Priority Technology and Other Needs for the U.S. Corrections Sector, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, RR-820-NIJ, 2015. lssue 4, February 2019: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR820.html

McDougall, C., Pearson, D.A.S., Torgerson, D.J. et al. (2017) // The effect of digital technology on prisoner behavior and reoffending: a natural stepped-wedge design. Journal of Experimental Criminology. December 2017, volumen 13, Issue 4, pp 455–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-017-9303-5

Hart, S. (2003) Making Prisons Safer Through Technology. Corrections Today, Vol. 65, N.º 2. The American Correctional Association, Maryland.

Brian A. Jackson et al. (2005) Fostering Innovation in Community and Institutional Corrections: Identifying High-Priority Technology and Other Needs for the U.S. Corrections Sector. Santa Monica, CA. RAND Corporation.

La Vigne, N. (2017) Harnessing the Power of Technology in Institutional Corrections. NIJ Journal. Issue 278, May 2017.

Harne, J. (2017) Identifying Technology Needs and Innovations to Advance Corrections. NIJ Journal. Issue 278, May 2017.

Liebling, A. (2011). // Distinctions and distinctiveness in the work of prison officers: Legitimacy and authority revisited. //European Journal of Criminology, 8(6), 484-499. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370811413807

Pedro das Neves works as government and multilateral organisations consultant/advisor on criminal justice systems innovation since 2002 in different continents. Pedro is the CEO of IPS_Innovative Prison Systems and ICJS_Innovative Criminal Justice Solutions Inc. He is the founder and chief-editor of the JUSTICE TRENDS Magazine and the CORRECTIONS. Direct online directory. Serving voluntarily in different boards, he is a board member of the BSAFE LAB of Beira Interior University; of APROXIMAR NGO; and chairman of EaSI the European Association for Social Innovation. In 2017, Pedro was recognised with the ICPA Correctional Excellence Award (Management and Staff Training). In 2018, was elected in Montreal as a member of the Board of Directors of the ICPA International Prisons and Corrections Association. Pedro frequently participates as speaker in conferences on citizen security, justice and corrections related events.

Torben Adams is Head of Division in Germany’s Federal State of Bremen Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs; among other tasks, he is responsible for CPVE programmes and initiatives, and advanced training for prison and probation officers. He started his career as a prison officer in 1997; his last post in prison was as governor of a juvenile prison. He has work experience in several countries in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. His main passions are criminal justice reform and prison development.

This article was originally published in JUSTICE TRENDS Magazine.